Our group screens for HIV in the TGH ED and have identified close to 300 HIV+ patients since May 2016.

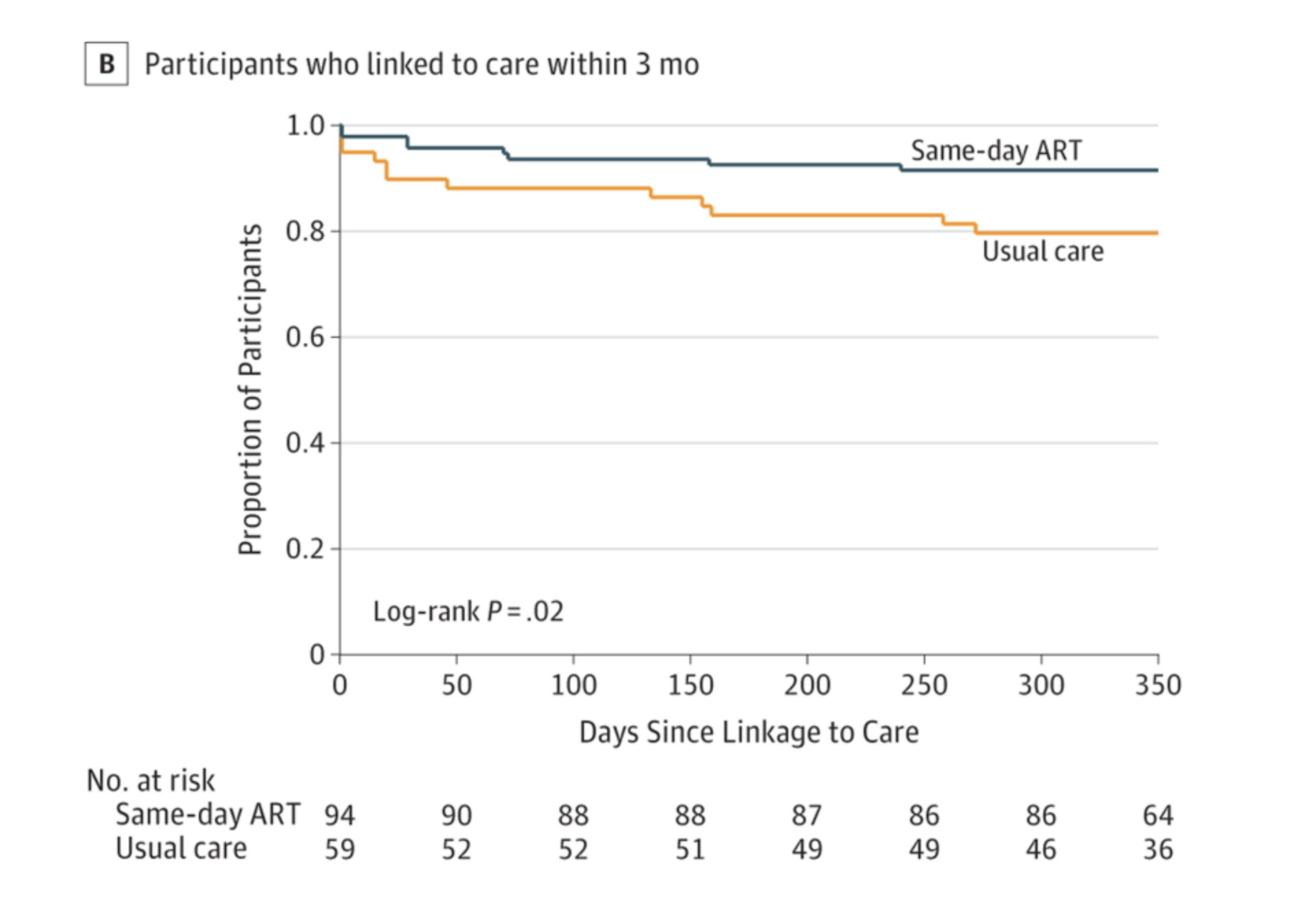

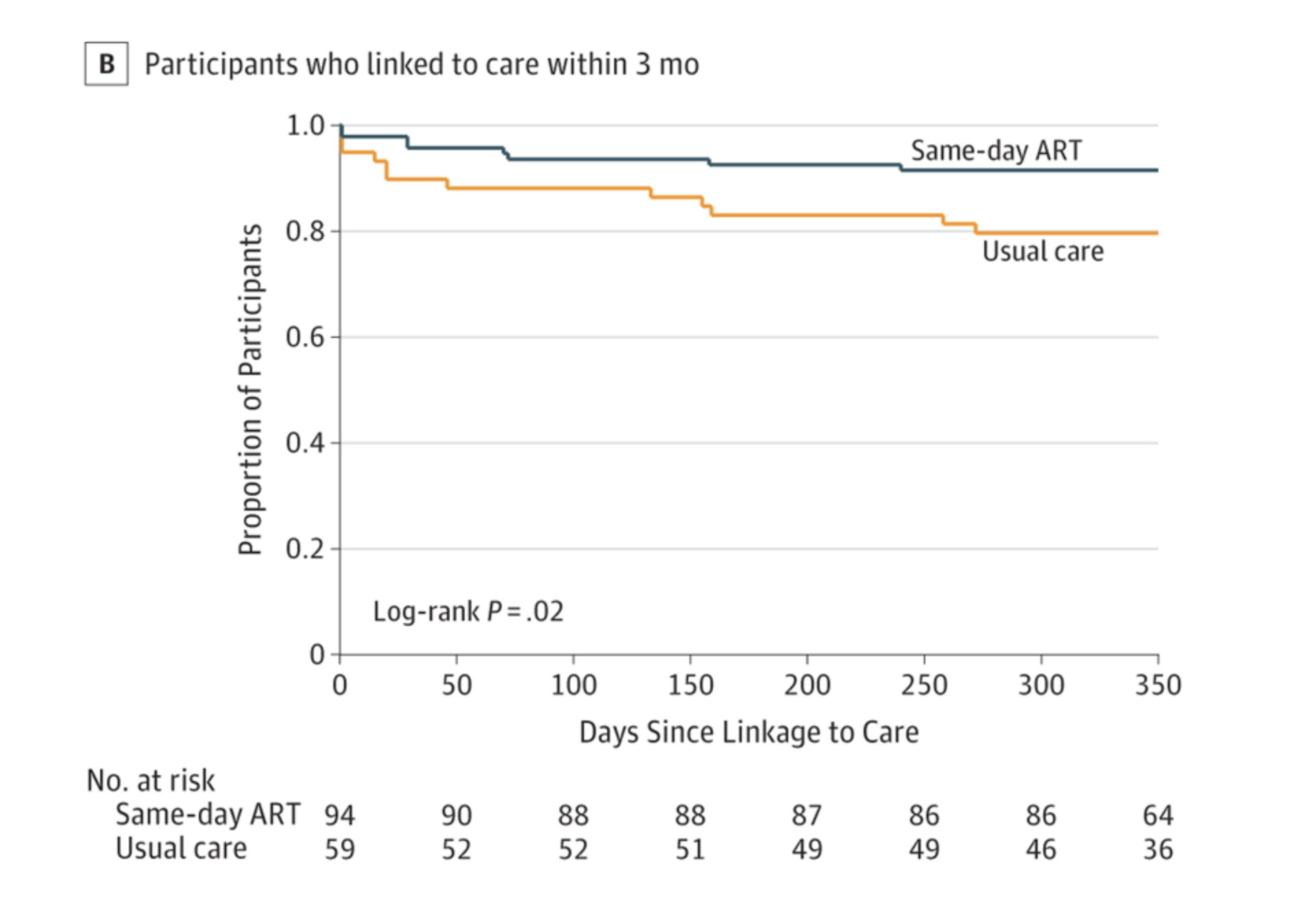

Currently, we do not initiate antiretroviral therapy (ART) when HIV positive patients are identified. However, this week, an article in JAMA adds to a growing body of evidence that ART should be and can be safely started during an acute clinical encounter based on global health data from the recently completed CASCADE Trial.

The authors conclude that:

“Conclusions and Relevance Among adults in rural Lesotho, a setting of high HIV prevalence, offering same-day home-based ART initiation to individuals who tested positive during home-based HIV testing, compared with usual care and standard clinic referral, significantly increased linkage to care at 3 months and HIV viral suppression at 12 months. These findings support the practice of offering same-day ART initiation during home-based HIV testing.”

This publication allows for a timely of our efforts to move HIV screening, linkage, and treatment forward in the ED setting.

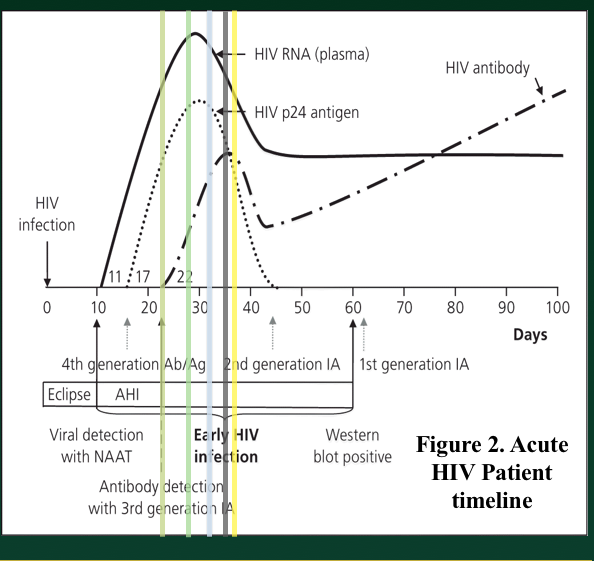

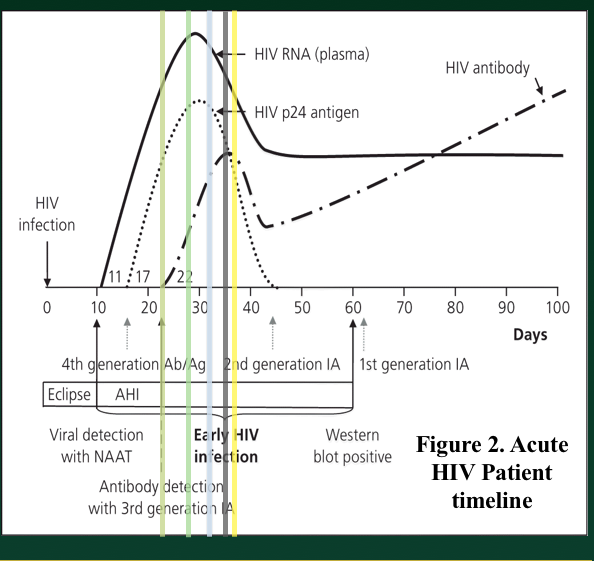

The HIV screening algorithm was revised in 2006 by the CDC and written for an asymptomatic screening population but is being utilized in the ED as well by our group and others, as requested by the CDC that individuals be screened at any point of entry into the health care system.

In our ED, we have modified the algorithm slightly in order to obtain a viral load as quickly as possible in patients that have a reactive screen/presumptive positive in order to act more quickly on results in a vulnerable patient population with a high pretest probability for disease. We do not wait for a confirmatory prior to running a viral load analysis of the patient blood sample.

A reactive screening test will ultimately result in a viral load test (either the confirmatory test will be negative and a viral load will be needed in this equivocal setting or the confirmatory test will be positive and a viral load will be needed by those who initiate treatment and in order to stratify the degree of HIV illness that the patient has at that point in time). Therefore, since we may only get one encounter with the patient in the ED and the result may presumed to be positive, we achieve the viral load immediately. This also helps prime our site for future pathways that might be adapted to same encounter viral load results that would allow definitive positive diagnoses and, potentially, initiation of therapy during that visit.

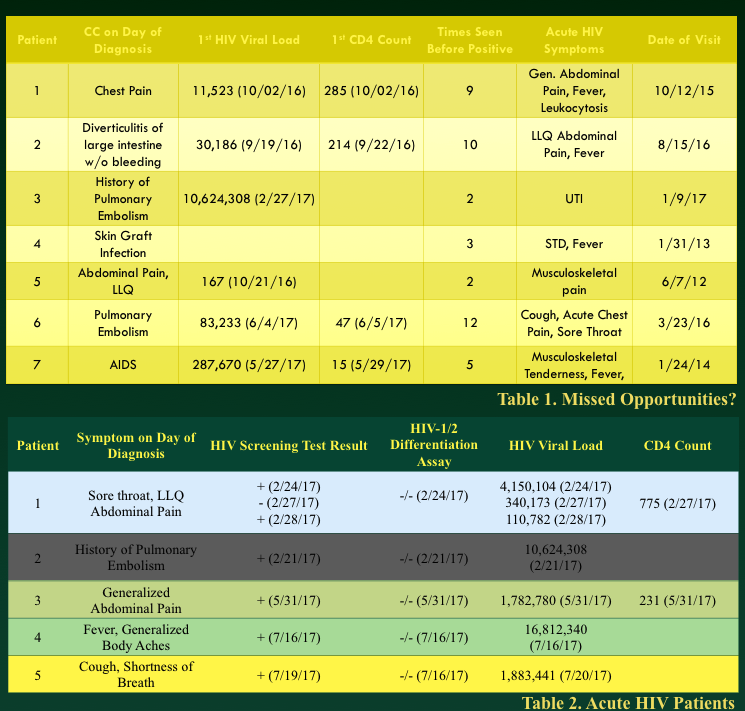

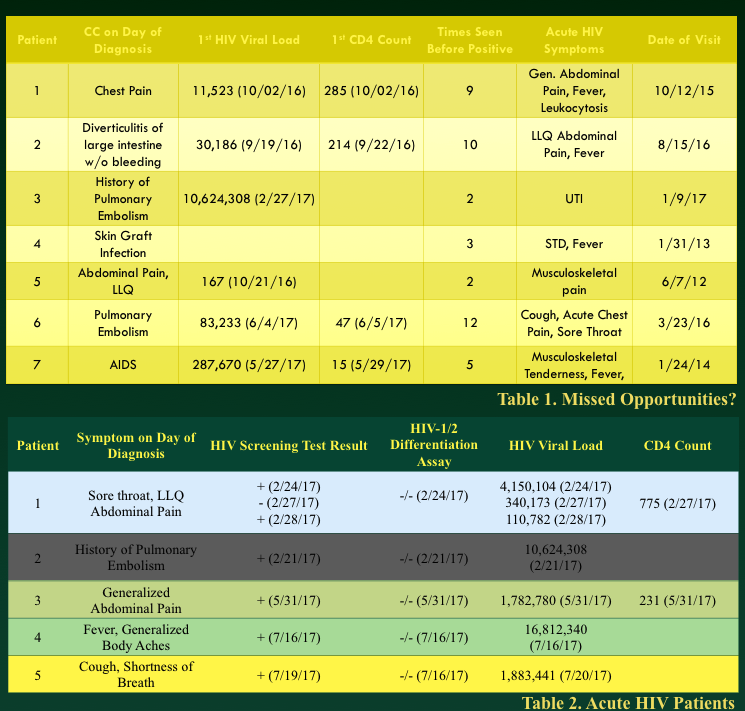

The difference, we are learning, is that an ED population undergoing HIV screening represents both asymptomatic patients as well as patients with viral like symptoms who may be presenting with HIV clinical seroconversion or even longstanding HIV.

As a matter of fact, some of our patients diagnosed during the first year of our screening project visited the ED in the prior year with HIV consistent symptoms and another group of our acute HIV+ patients (positive screen, negative confirmatory test, positive viral load) also came in to the ED on day of diagnosis with symptoms consistent with HIV.

Above poster presented at Symposium by the Sea 2017 by Sri Palakurty

Our work now centers not just on linkage to care, but also trying to create a highly reliable system of result interpretation in the ED given the pretest probability of a patient during a specific clinical encounter.

In other words, we would like ED physicians, including myself, to trust a positive result is positive. However, the quick turn around time of the HIV Ab/Ag screen means that the effective false + rate (+ screen, neg confirmatory) has been over 10% (i.e. 10% of those with a reactive test will go on to have a negative confirmatory test). In addition, we have learned that our patients do seek diagnosis of HIV symptoms in the ED when HIV status is unknown. Given the acute nature of presentation, we also fear that a patient may present in the HIV Ag/Ab non-detectable window and haven even discovered a patient with a negative screening test but positive viral load.

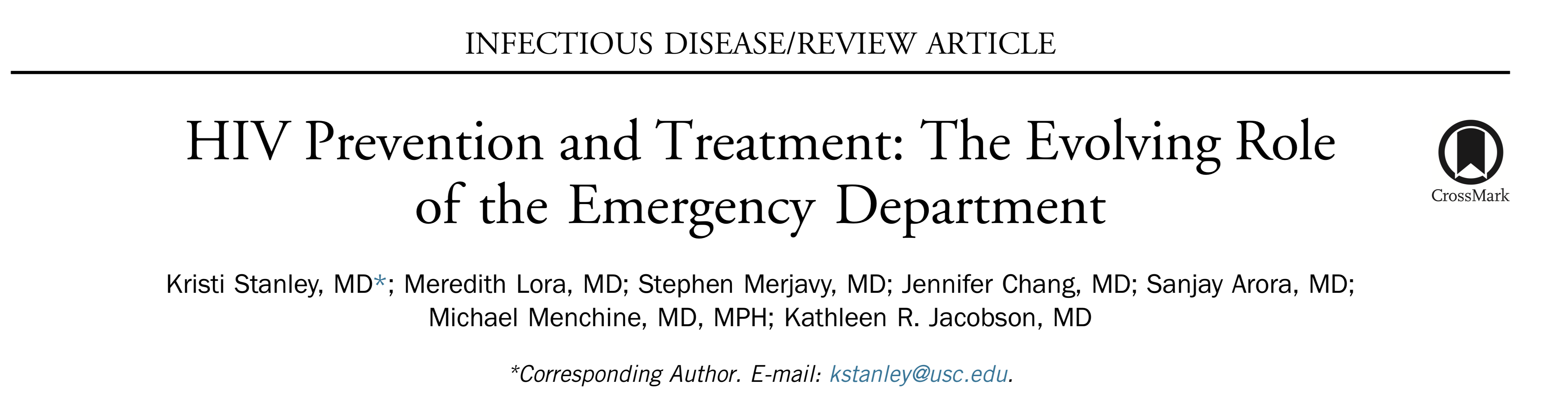

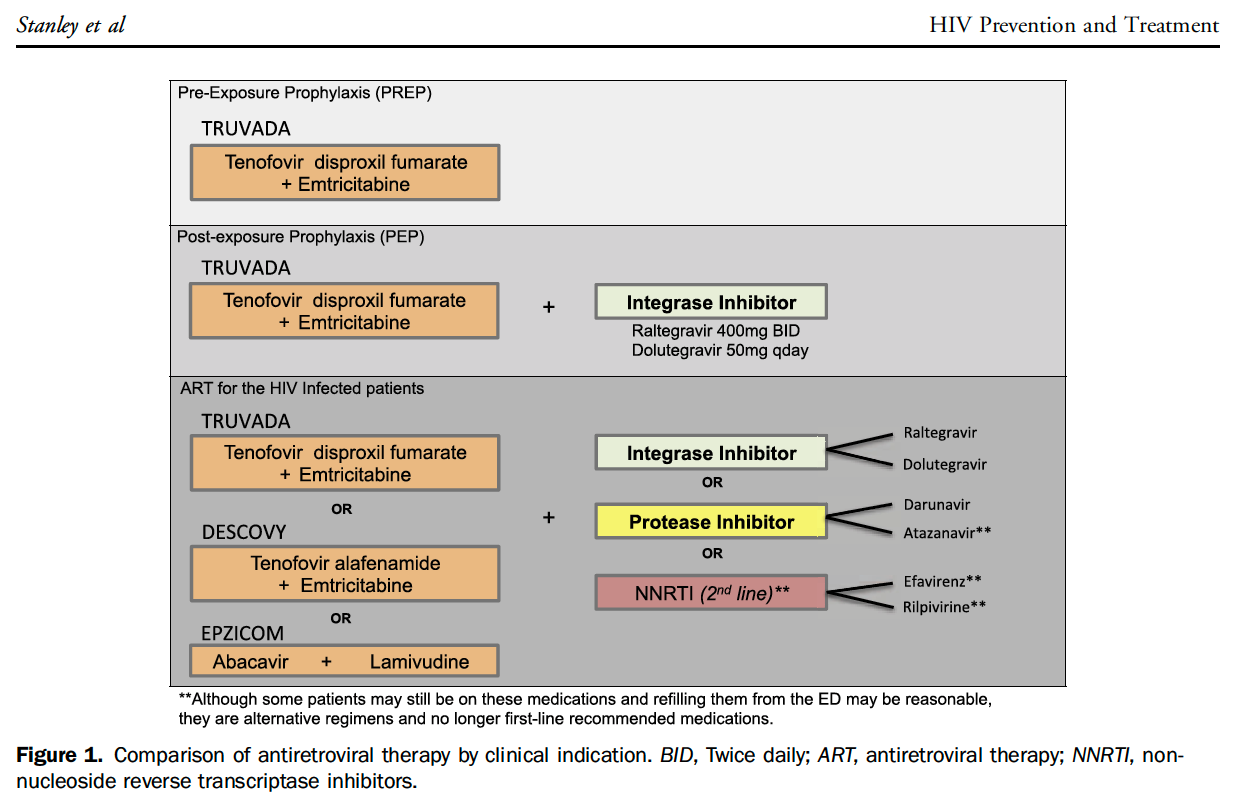

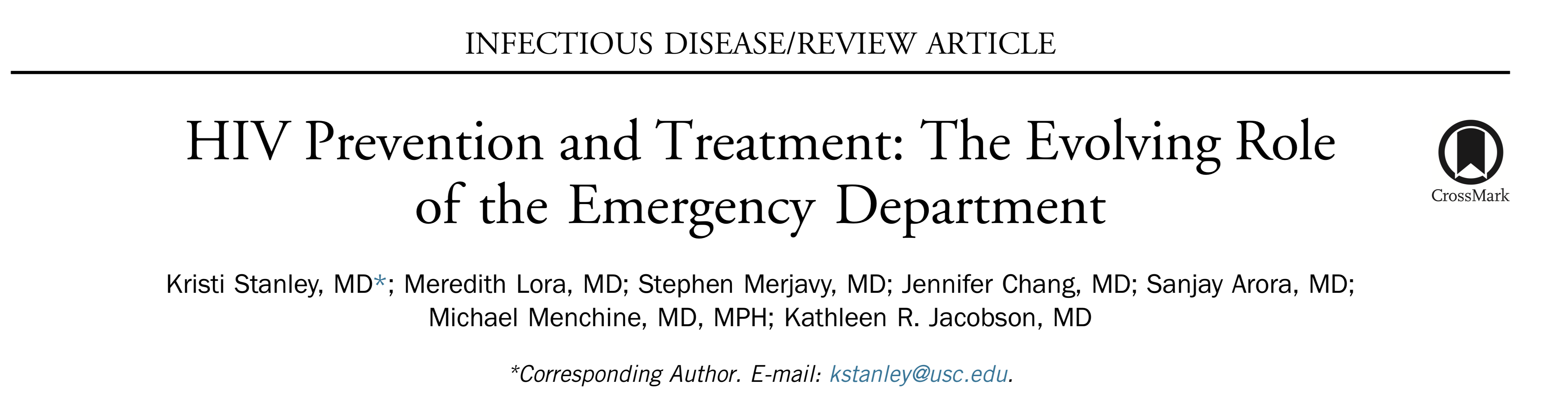

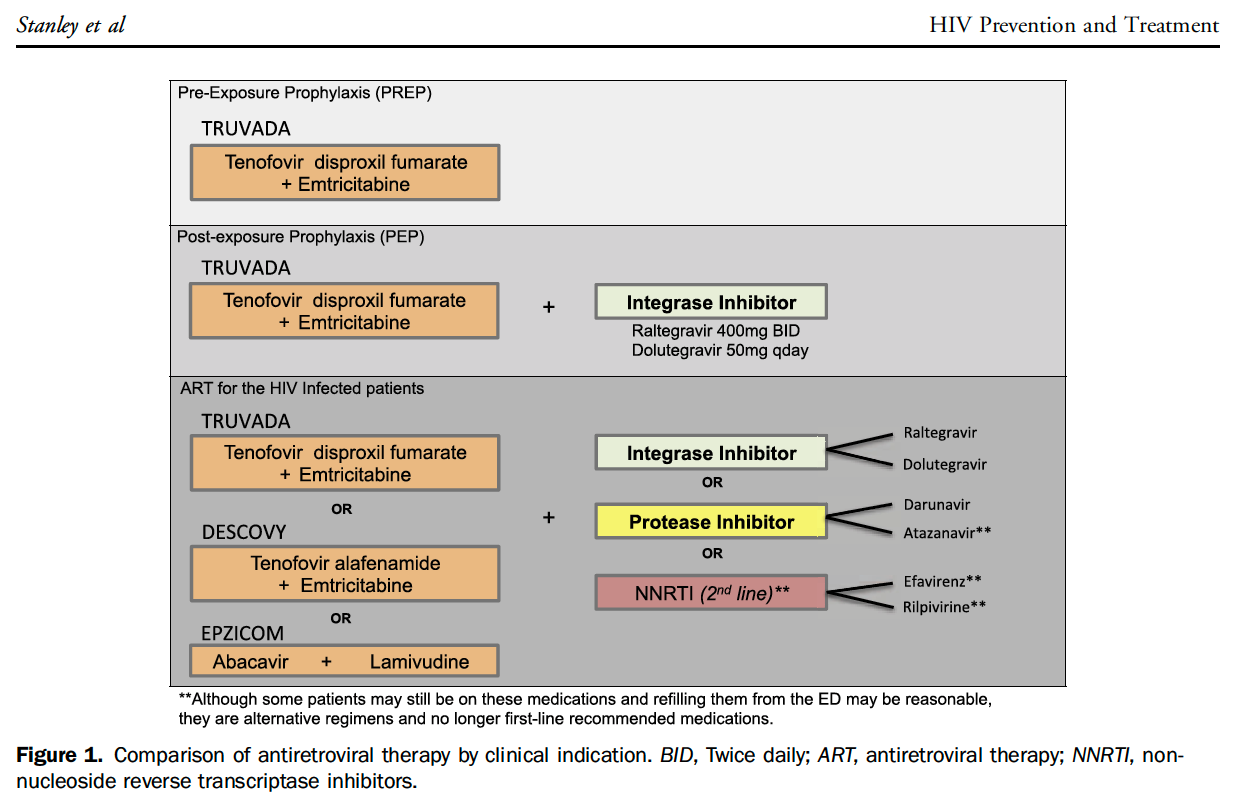

Thus, the quicker we turn around viral load results, the more rapidly we can place patients on HIV treatment with antiretroviral therapy (ART). While prior concerns regarding resistance were expressed in earlier days of therapy, the high prevalence in the United States of HIV-1 makes these concerns less relevant. In addition, prior work on preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and on-demand prophylaxis has not demonstrated patterns of resistance even when drug is taken in a staccato nature.

Therefore, our group feels strongly that rapid HIV viral load testing in high risk individuals and individuals with symptoms consistent with HIV (i.e. diagnostic test in stead of screening) is critical to increasing the ED uptake of an HIV screening and treatment strategy. The development of HIV PCR test kits that turn around times less than 3 hours and run on a single cartridge are especially interesting to our efforts.

In addition, we feel that physicians should be comfortable with the results of HIV testing in the ED – meaning that the results are highly reliable and can be acted upon by prescribing ART in the acute setting, assuming there is no evidence of TB (still a concern for some of the medications but can easily be discovered through history and physical exam during the same encounter).

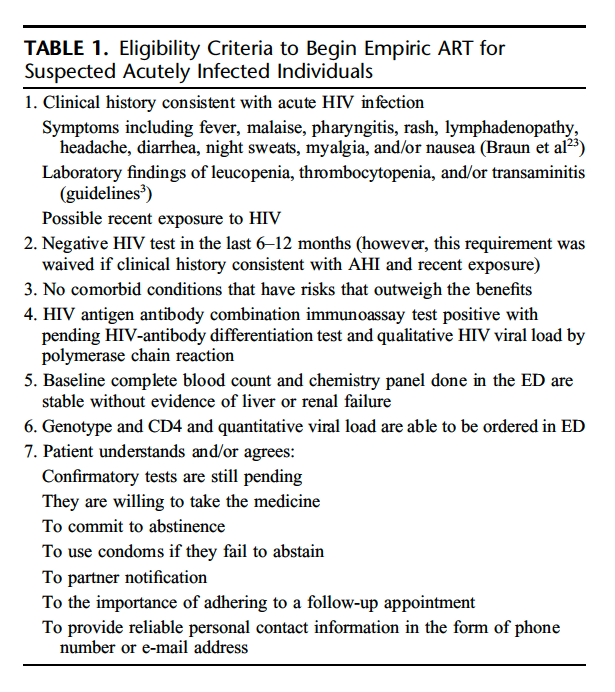

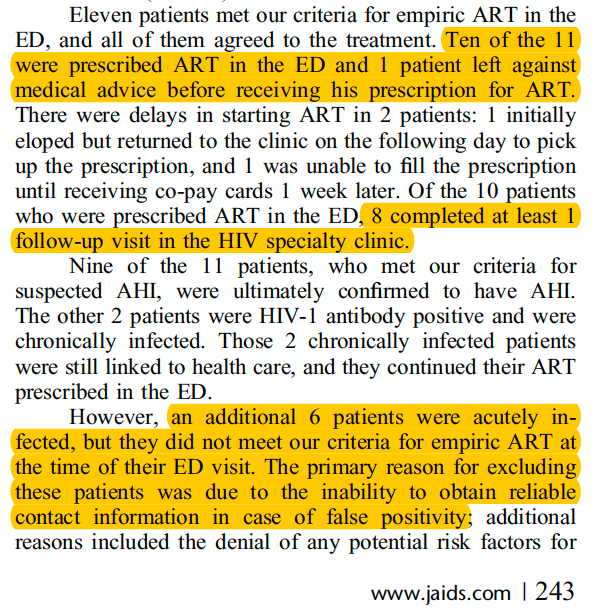

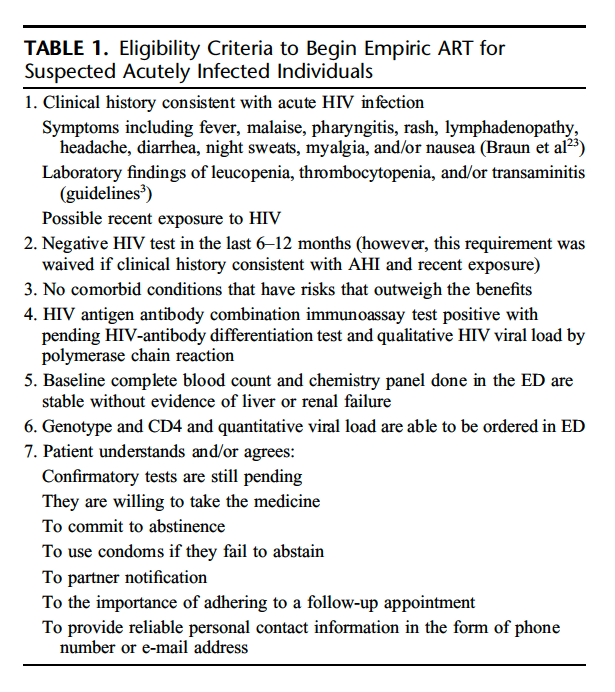

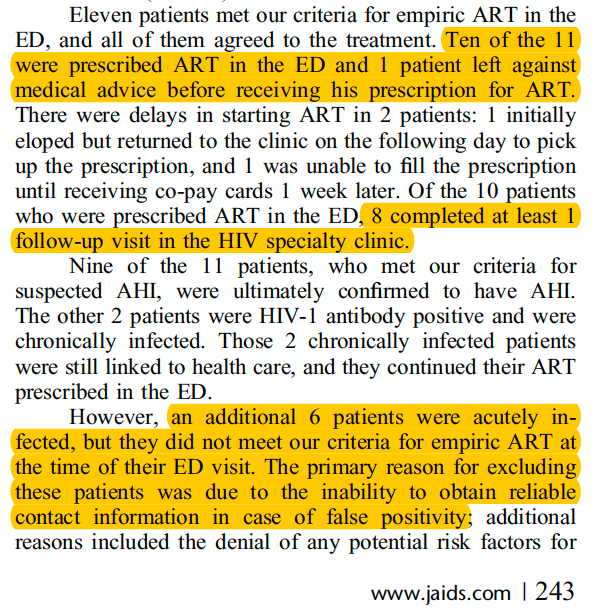

The ability for ED physicians to successfully prescribe and initiate ART has been demonstrated previously.

Barriers to ED initiation of therapy are rooted in prior complexities of treatment and persistent assumptions regarding challenges in starting therapy. Stanley et al., reviewed some of these myths in an important Annals of Emergency Medicine paper in 2017.

One of the most prevailing myths leading to difficulty starting acute HIV treatment programs revolves around the issue of drug resistance in patients that do not maintain their drug regimen.

“Certain conditions such as nonadherence allow the HIV virus to mutate to ‘beat’ or become resistant to the drug regimen that the patient is prescribed. Earlier drugs were highly susceptible to resistance; very few mutations could

easily knock out an entire drug and other drugs within the same class. Drug failure would quickly lead to virus resistance, which would limit future therapy options”

“As a consequence, physicians were worried about starting medications in patients for whom adherence might be a question for fear of hastening these resistance patterns.”

However, the success of PrEP and on-demand PrEP therapy as well as properties of new drugs such as protease inhibitors, seem to have a much higher barrier to resistance and the benefits of initiating drug likely outweigh any perceived, small risk of developing an unfounded drug resistance using newer agents.

When I was training, many patients did not start therapy until their CD4 counts dropped below 500 cells/mm3. However, the ability to decrease transmission and the improved side effect profile of ART in 2018 has made the time to initiate drugs clearly as early as possible. In 2015, the Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START) was published, lending strong evidence to early drug initiation.

If Emergency Medicine physicians can deal with the complexities of CAP, HCAP, HAP, & VAP antibiotic selection as well as myriad other difficult drug dosing decision made daily during a clinical shift, fairly simple algorithmic dosing will not be complicated in the future.

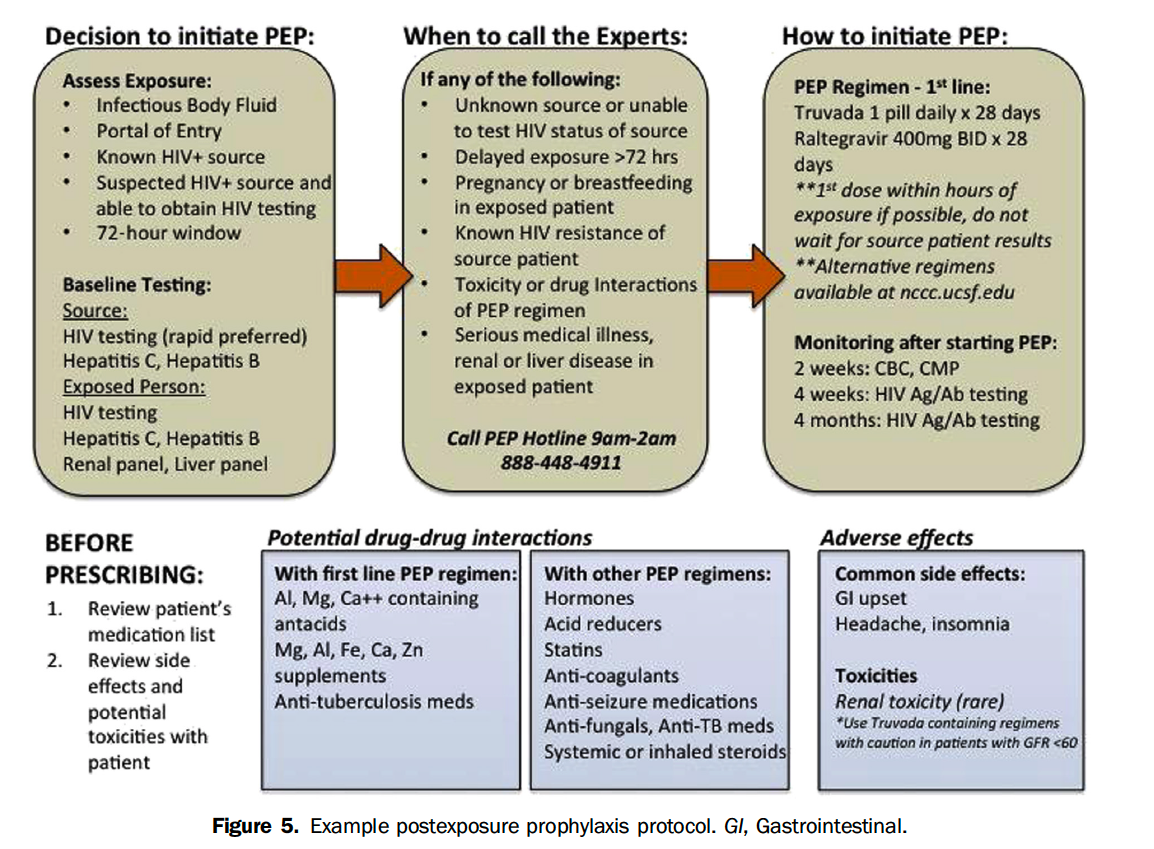

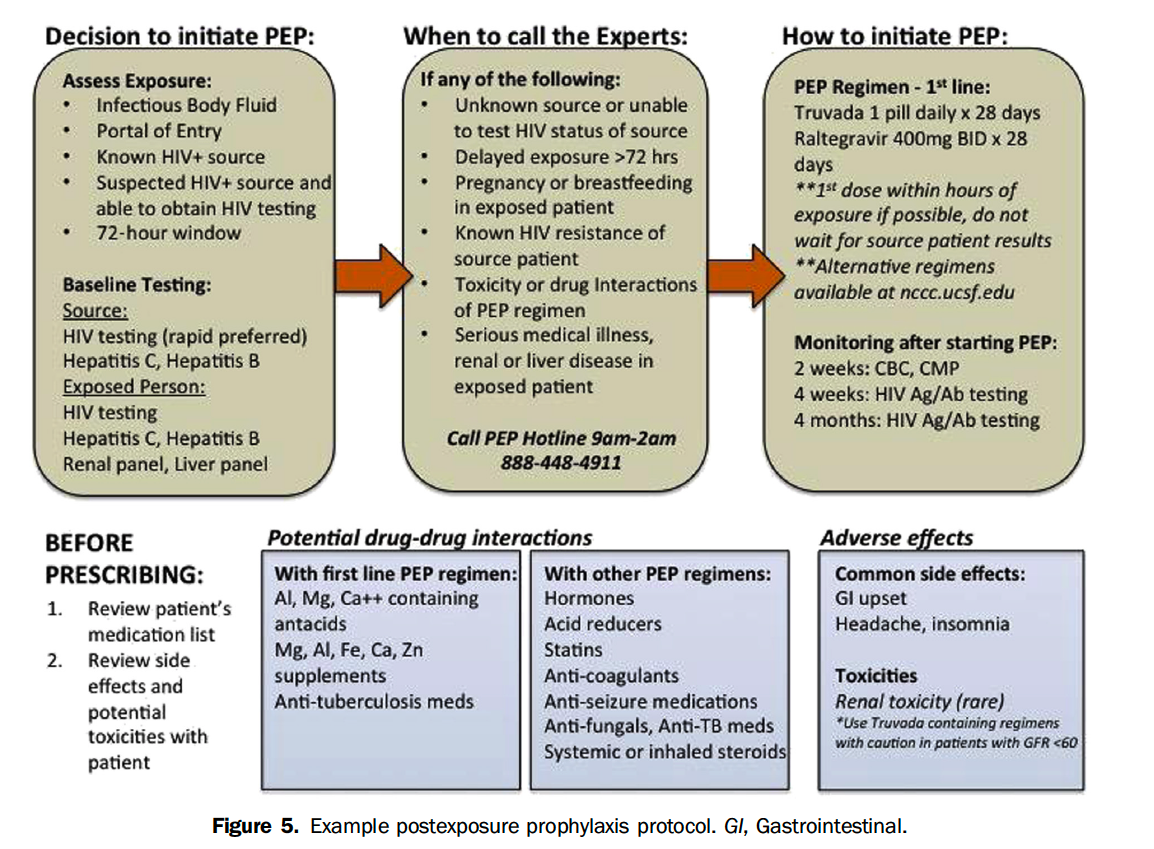

At our institution, the infectious disease team works with ED leadership to maintain an occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (oPEP) pathway. However, non-occupational PEP (nPEP) is not well delineated.

Currently, our HIV group is working with an adolescent medicine physician, Diane Straub, MD, MPH, who recently developed a nPEP clinic pathway which allows access to drug for even those with no insurance funding using a commercial retail pharmacy.

Another nPEP pathway was published in the above mentioned Annals article from 2017 and is also easy to follow once implemented.

The existence of CDC guidelines for nPEP and PrEP make pathway implementation in an ED potentially filled with less barriers than initiating ART in all patients with an acute HIV+ diagnosis .

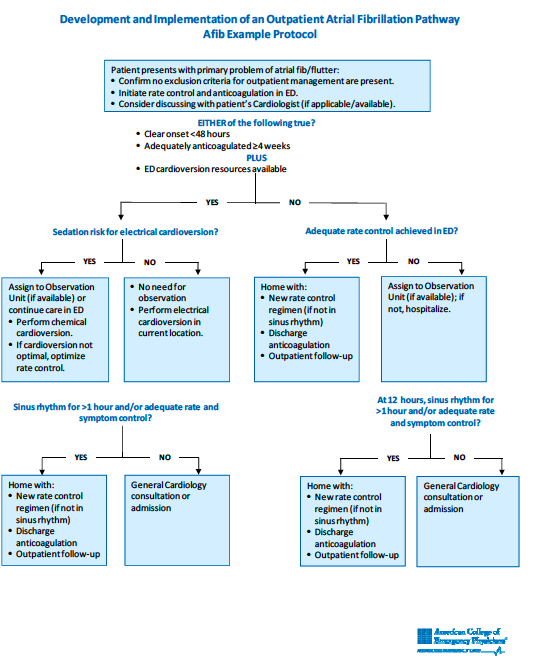

However, the evidence continues to mount that the benefits of initiating ART in the acute setting outweighs the risks. In the future, a specific ED based screening algorithm that differentiates patients that need HIV testing secondary to clinical concern would be useful. That future algorithm should also include specific ED based strategies for oPEP, nPEP, PrEP and initiation of ART.

The CASCADE trial published in JAMA was also accompanied by an editorial.

This recent publication of CASCADE and the same issue editorial comments make a clear case in the context of other acute HIV literature in the setting of newer ART that we must continue to move screening, diagnostic, linkage and treatment strategies into new directions to ultimately eradicate HIV.